Feature | Going beyond infrastructure gaps to improve trade competitiveness in Sub-Saharan Africa

In 2006, I was requested to contribute to an analysis of the impact of transportation costs on trade competitiveness in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Back then, I was working as an intern in the World Bank (WB) Africa Transport Unit with Gaël Raballand, a senior WB economist, to conduct a cost/benefit analysis (CBA) of a US$ 200 million regional transport project in Central Africa (Cameroon, Central African Republic and Chad). The project included investments in road and rail infrastructure, in border posts, and few innovative soft components to facilitate trade movements in the region (1). Six years later, the project is still on and has been extended three times to reach a total approved financing of more than half a billion dollars to date.

Among the many questions addressed during such a CBA exercise (2), the most interesting one for an analyst is probably the end one: “Is the project worthwhile”. Despite the convincing picture that CBA analyses of most development projects would provide, with double-digit economic rates of return, economists know that figures can be misleading. The issue is not that potential benefits are low; infrastructure constraints are so critical in SSA countries that the return on infrastructure investments is virtually higher than in any other region. The main issue is that the political economy of the future use and management of the new or rehabilitated infrastructure is so complex and depends on such a wide array of factors (economic, political, social, environmental, organizational, etc.) that the probability that such economic benefits materialise becomes very tentative.

With regards to transport investments in SSA, what we came to understand through our extensive fieldwork and analyses is that improving road or rail infrastructure was seldom the stepping stone for an effective development outcome, and this triggered a series of research initiatives that would come up with “very thought-provoking ideas”(3).

In a first study on transportation costs and tariffs, we used an extensive survey of trucking companies and truckers to demonstrate that there is little correlation between transport costs and prices in SSA countries. Additionally, our findings highlight that market environment has a strong impact on the efficiency of transport operations, that reducing border crossing time would have in few international corridors a much stronger impact on prices than improving road condition, and that lowering fuel prices or working on compensatory schemes to help break regulatory status quo are priority actions that have been neglected in the past. These findings came as a challenge to authoritarian views that Africa is first and foremost suffering from an infrastructure gap that is the consequence of decades of under-investment, and that the priority for now and for the next decades is to invest hundreds of millions to bridge this gap.

Later on, Gaël Raballand and others would conduct a second study to specifically address the case of landlocked countries – countries that have no access to the sea and are therefore dependent upon land transit through neighbouring coastal countries for the entirety of their international trade. The study empirically demonstrates that landlocked economies are primarily affected not only by high transportation tariffs, but also by the high degree of unpredictability in transportation time. The main sources of costs are not only physical but include widespread rent activities and severe flaws in the implementation of the transit systems, which prevent the emergence of reliable logistics services.

These two studies triggered a third one that we recently published as a report addressing in part issues of high transportation tariffs and long transportation times at what happens to be the bottleneck of transportation chains in SSA: the seaports.

These two studies triggered a third one that we recently published as a report addressing in part issues of high transportation tariffs and long transportation times at what happens to be the bottleneck of transportation chains in SSA: the seaports.

Our report, titled “Why does cargo spend weeks in Sub-Saharan African Ports?”, is not economic research by academic definition. Most of the work Gaël Raballand, myself and a few other consultants have performed in the last two years to try and answer this question has been equally informed by our own experience, consultations and field interviews than by thorough analytical work. And this is precisely because we start our research by the fascinating observation that more than half of the time needed to transport containers from ports to end users in SSA countries is spent not in motion, but idle in port container terminals. The question of transportation times has therefore at the onset little to do with transportation systems.

To address the cargo dwell time issue in SSA one needs to understand the ins and outs of cargo clearance in SSA ports and combine – at best – analyses of port operations, customs processes and trade logistics to identify the key constraints and the possible solutions. Data and statistics are indispensable however, and we have invested a lot of efforts in collecting data across eight countries, using comprehensive customs and port operator databases as well as in performing a wide survey of manufacturers and retailers with the help of a leading global survey company. The results of the quantitative work have then been subject to a comprehensive consultation and interviewing exercise to challenge and fine-tune our early conclusions.

From a methodological standpoint, two of the most important takeaways from the report are that (i) complex trade logistics issues can only be tackled from a systemic perspective, and that (ii) the analysis of the time spent by containers between unloading from the ship and exit from the port (what we call port dwell time in the research) requires a breakdown of sequential and parallel operational, transactional and storage times (4).

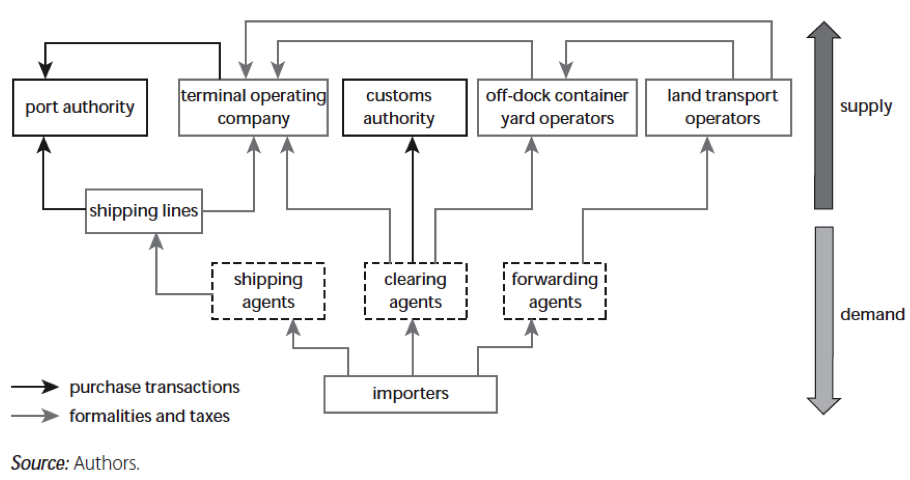

In Chapter 2 of this report we present our port system model for container imports (see Figure 1) that distinguishes between a series of “suppliers” such as port authorities, terminal operating companies (5), customs authorities or shipping lines, and “users” that are not only the importers themselves, but also importantly their shipping, forwarding and clearing agents that consider both the importers’ requirements and their own interests when choosing between alternative port clearance options. Consideration of this complex map of interests is critical to understand how the system operates and how the system would evolve if a major change such as a massive infrastructure investment happens.

We use the breakdown of dwell time between different constituents to analyse the data collected on the 8 different ports in Chapter 3. The findings are compelling, with average delays of more than two weeks, with the exception of the Durban port in South Africa that emerges as the unique example of an efficient gateway. Detailed statistical analysis is conducted to not only benchmark the different ports, but also to perform detailed case studies for each of the selected ports.

The case studies have led us to discover that demand is the main driver of inefficiencies in the system, and we dedicate a full chapter (Chapter 4) to analysing this particular factor. The large survey of manufacturers and retailers brings fascinating perspective on their own priorities and decision process, at a country level, but also at an industry level and at a “market-size” level – since small retailers happen to behave very differently from large manufacturers or wholesalers. We bring in our own model of demand for cargo dwell time that we have also presented in a separate recently published working paper.

The interesting part is then to derive practical policy recommendations for decision-makers and development institutions that are based on these various models and data sources. We attempt to do so in Chapter 5 by first drawing the picture of the different impacts of the long cargo dwell time issue for decision-makers and development practitioners to change their perspective on the trade logistics issues in the continent. There are indeed paradoxical conclusions from the demand model that suggest, for example, that long dwell time can be in the interest of some parties. In the case of Cameroon for instance, it is not until the 22nd day of storage that clearing containers out of the port is economically preferable for those importers that have to store their cargo for long weeks in private warehouses, and in most ports, the escalating tariff structure of port storage fees suggests that some operators might appreciate long dwell times if the port does not operate close to capacity. The big picture, however, is that long port dwell times are very costly for SSA economies and we estimate that a port dwell time of 20 days (as opposed to 7 days) for container imports would be responsible for a reduced trade of up to 5.4% of total imports in Cameroon.

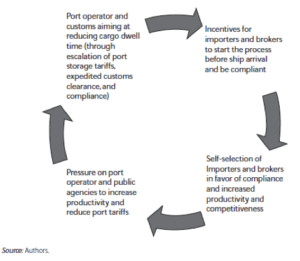

When it comes to possible solutions, tricky political economy issues have to be solved. The vicious circle of a series of transactions and bargains that lead to long dwell times and rent-seeking has to be broken and replaced by a virtuous circle operating efficiently in the port of Durban (see Figures 2 and 3). Cooperative behaviours have to be facilitated through formal or informal meetings of stakeholders at the decision-making level. The use of electronic system capabilities (such as anticipated customs declarations) has to be encouraged and catalysed. And successful models of incentives have to be used to encourage and spread good performance in the system.

There is much more to say and do about the port dwell time issue in SSA. The research described in this report was in effect a contribution to understanding the relevant and complex questions but without necessarily providing all the answers. However, as we did in the two previous reports, we hope to have shed some light on a very critical trade competitiveness issue in SSA countries and, at the same time, we advocate a change of perspective on trade logistics issues in SSA. We also want to advocate a change of perspective on the economic issues faced by SSA countries: solutions have to be nuanced, informed by a very detailed knowledge of the stakeholders involved and the complex map of their interactions, by a knowledge of the sequence of operations and transactions that constitute or affect the use of physical infrastructure, and by an analysis of market incentives and competition in the considered countries.

Whether in SSA or in other developing countries, including Algeria, costly physical interventions can be attractive solutions for development banks or governments, but solving the structural issues first is indispensable or else money would simply be wasted with no or little impact on the welfare of populations. How these issues are solved is obviously an open question, with a variety of opinions on the respective role of stakeholders in the public and private sectors. In the end however, what matters most is that incentives of good performance spread within the system, as they have already been doing so in some countries.

Notes

(1) Inter alia: technical assistance and equipment to interconnect the customs administrations, assistance to the establishment of a regional corridor management authority, support to regional economic community (CEMAC) to establish a new regional transit regime, etc.

(2) Refer to this link for a discussion of these issues and to this link for the reference WB CBA methodology.

(3) Vijaya Ramachandran, commenting our book on the blog of the Center for Global Development.

(4) Definitions p. 19 of the report.

(5) Note that most of the ports in SSA are privately operated by concessionaires.

About the Author