Interview | Artificial antibodies for self-testing technologies

Each year, MIT Technology Review 35 Innovators under 35 recognises the achievements of young innovators from both industry and academia whose work show potential to influence or profoundly transform their fields. In this year’s edition, Dr. Abdennour Abbas received an Honourable Mention for his research on artificial anti-bodies. Inspire Magazine spoke with Dr. Abbas about his invention and how it influences the field of diagnosis technology as well as its potential for contributing towards improving future healthcare systems.

Inspire Magazine: Many thanks for speaking to Inspire Magazine. Can we start by asking about your scientific journey and how it led you to the USA?

Abdennour Abbas: I was born and raised in Algeria. I graduated in Biochemistry in 2003 from the University of Tizi-Ouzou, and moved to France shortly thereafter. My parents made tremendous efforts to make that transition possible. After obtaining a Master in physical chemistry of biological systems from the University of Lille, I received a doctoral fellowship from the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research and obtained my PhD in Materials Science and Engineering in October 2009. Three months later, I moved to the United States for my first job as a postdoctoral research associate at the University of California and then at Washington University. A month ago, I accepted a faculty position as assistant professor at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, where I will be soon directing the Biosensors and Bionanotechnology laboratory.

IM: You recently received an honorable mention in the MIT Technology Review 35 Innovators Under 35 (TR35) for your work on artificial antibodies. Many congratulations for this wonderful achievement. So, what are artificial antibodies and how can they be used for self-diagnosis?

Abdennour Abbas: Artificial antibodies are tiny structures made from polymers by using a technique called “molecular imprinting”. These structures exhibit affinity and recognition abilities towards specific molecules, exactly the same way natural antibodies interact with pathogens. The concept is very simple but its implementation at the nanometric scale is extremely challenging. Let’s say you want to detect a cancer biomarker in a patient’s urine. What we do is to take the biomarker of interest and use it as a template to create imprints on the surface of a functional material. It is like creating imprints of your hands on modeling clay. These imprints will then have a complimentary shape and reactive surface that enables them to capture the same biomarker again. The novelty in our work is the successful implementation of this technique on the surface of gold nanoparticles. This is important because gold nanoparticles can be used as a transduction platform, which means we can see the moment when the artificial antibodies capture the biomarkers by shining a laser at the nanoparticles.

IM: How did you end up working in this area and how did you go about developing this particular idea?

Abdennour Abbas: My initial education interest was in biochemistry and molecular biology which were very popular in the 1990s due to the promises of the genetic revolution. A decade later, the employment market was flooded with biologists and a new paradigm was taking shape by the emergence of bionanotechnology. Bionanotechnology is a field that uses nanotechnology to address challenges in biology and medicine. I was very excited by the idea of addressing the same problems from the nanoscale perspective. I have then decided to focus my Master and PhD studies on this emerging approach. When you are a student, it is important to keep track of changing trends in both science and the employment market, and make your education choices accordingly, because by the time you will be graduated, things would have already changed.

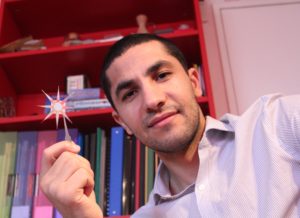

Dr Abdennour Abbas showing a paper-based biosensor with a star-like shape. This is the most sensitive paper biosensor reported so far. The sample to be analyzed is put at the center of the star. The deposition is immediately followed by a spontaneous separation in different arms and motion of the sample towards the tips, where gold nanoparticles are localized. This concept enables the separation of the different components of a complex sample and their preconcentration 1 billion times at the tips, thus providing unprecedented sensitivities

The second part of your question is about the development of artificial antibodies. Here is the main motivation of this work: just like phones started as big devices used in a public phone box and later became personal items, it appears increasingly clear that diagnostic technologies will follow the same path to provide hand-held and affordable products for home self-testing. However, the biosensors currently used for self-diagnostics suffer from low sensitivity, short shelf life and relatively high costs. Since a significant part of these hurdles is caused by the use of natural antibodies, the idea then was to make cheap artificial antibodies on the surface of gold nanoparticles, which brings the cost down and significantly improves the shelf life.

IM: At best, what would the outcome of this research be? does the technology behind this research have any other potential applications?

Abdennour Abbas: This research is only a small example of an emerging direction and a growing focus on self-testing and point-of-care technologies. I understand your question is about a specific research, but the challenge is much bigger than that. Here is the big picture: a decade ago, biotechnology was the big revolution in healthcare, which provided affordable vaccines, antibiotics and drugs. Today, nanotechnology is radically changing the way how we detect, treat and prevent diseases. There are already companies that offer to sequence your DNA and detect inherited health risks for $100, and others offer self-diagnostics tests that allow people to detect AIDS at home for $40 or less. Even if some of these technologies are still relatively expensive and sometimes controversial for ethical reasons, there is no doubt they are opening up new perspectives for a preventive healthcare system. Preventive care technologies can save lives and billions in public spending, and thus should be a major part in any healthcare system reform or biomedical research program. Every government is complaining from the unmanageable healthcare costs but every new reform is rebuilding the same model with a different funding plan. I have said this before in many occasions: it is not a budgeting problem. The only way to build a sustainable healthcare system is to shift our focus from a reactive care industry to preventive care technologies. Genetic screening, implantable medical devices and self-diagnostics are good examples of these sustainable solutions for a new healthcare model.

IM: Often patients seek medical help for one reason, but end up being diagnosed for something else as a result of the doctors investigations. With this in mind, do you think it is safe to empower patients with this technology? i.e. Could it result in misdiagnosis? Or perhaps lead patients to avoid going to see a doctor and hence potentially miss out on seeking crucial medical help?

Abdennour Abbas: You raised a legitimate concern. I think it is always useful to empower people with technology, as long as it is well regulated. Self-testing should not be seen as a replacement for conventional diagnostic methods or traditional visits to the doctor. This is a complemenraty tool designed to help people monitor their health in a regular basis and detect any change as soon as it happens. The earlier you detect a disease, the cheaper and faster the treatment will be. Also, this is a good alternative for people who are not comfortable visiting a doctor for privacy reasons such as in AIDS and STI testing, or people in low-resources countries who do not have access to doctors the same way we do. Additionally, future developments will provide multi-pathogen detection, meaning that people will have the ability to use a single test and get results for a wide range of diseases.

IM: How about the potential of deploying this particular kind of technology in Algeria, how do you think it can be realized, if at all? And how can it be leveraged?

Abdennour Abbas: The good thing with this kind of personalized medicine is that it is based on affordable and accessible technologies. However, any development in this direction requires an adequate regulatory environment. Last year, the FDA approved the first in-home HIV Test in the US. France did the same thing a few months ago. For Algeria to keep pace with these changes and rapidly benefit from them, it needs first to set up a good regulation to favor their use and development. This is the good time to do it. The rest is the job of engineers and entrepreneurs.

IM: What other lines of research are you involved in, and how do they relate to the technology you developed for self-diagnosis?

Abdennour Abbas: Biosensing is a very interdisciplinary field. The same technologies developed for diagnostics can be applied to many other problems, including the detection of water contaminants and bioterror agents. We are also working on the development of personal devices for the detection of food spoilage in order to prevent food poisoning. The overall purpose of our research is to empower people with all kind of portable or wearable devices for a more effective and timely control over their health, food and environment. Beside the applied research, we try to understand fundamental problems related to biosensors and bionanotechnology.

IM: Many thanks for taking the time to speak to Inspire Magazine, we wish you all the best with your future endeavors.

Abdennour Abbas: I believe your team is the one that deserves thanks and praise. You are doing a wonderful job by the launch of Inspire Magazine and the Best Algerian Paper Award. I understand from your website that you are running this organization on a voluntary basis and without any external support. I am impressed but also saddened by this. Your organization is exactly the kind of initiatives that deserves to be fully supported and funded by the Algerian embassy and the ministry in charge of the Algerian diaspora. I can only imagine all the good things you can do with more support.

2 Comments so far

Event Report | Positive action: TEDxAlger 2013 | Inspire MagazinePosted on 3:09 pm - Oct 2, 2013

[…] fields were announced gradually during the promotional campaign of TEDxAlger. The scientist Abdenour Abbas, the humanist Nassima Dzair, the young activist Taki Eddine Djeffal and the famous Andalous […]

About the Author